First World War

Artifact W1-03: Address to 37th Signal Regiment Dinner

Submitted by BGen Jack Partington, RCAF (Ret.)

“You have been celebrating your 110th anniversary as a Signals unit and I am honoured to be included in the ceremonies and this fine Regimental Dinner. But there is another date that is also important to your heritage as Signallers. It was 100 years ago this August 4th that Great Britain declared war on Germany. As part of the British Empire, Canada responded immediately, and that same month the St. John Signals Company departed by train to Valcartier to join the First Canadian Expeditionary Force.

The Expeditionary Force, made up of 33,000 Officers and Men as well as 6000 horses, sailed from Montreal on September 30th, 1914. The convoy of 32 transports gathered in Gaspe Bay and formed into three columns, with British Royal Navy cruiser positioned at the front and rear of each column for protection from German submarines. They departed Gaspe on October 3rd heading east for England. On board the Cunard liner “Andania”, Number 6, Starboard column, were the following Expeditionary Force units: 50th Gordon Highlanders, 72nd Seaforth Highlanders, 79th Cameron Highlanders, 91st Argyll Highlanders, 14th Battalion Victoria Rifles and the 1st Divisional Signals Company, commanded by my grandfather, Major Thomas Edward Powers, of St. John, New Brunswick.

When they left St John the Signals Company was already ten years old, and most of the soldiers had known each other at home or had trained together in St John and Valcartier. Major Powers knew all 46 of them well – he was by then 40 years old, and had been a teacher in St John as well as the Signals Company Commanding Officer and, as one can tell from the family scrapbook, a father figure to many of them. In letters written home, the St. John Signallers often referred to each other, such were the bonds of friendship among the soldiers. These letters were often shared with other St. John families, and the newspapers. Such was the trust among families on the home front.

The convoy arrived at Portsmouth two weeks later (Oct 17th telegram) and settled in to the British Military camp at Salisbury Plain, where they trained and exercised for four months.

They were eventually deemed ready for the front following a Royal Inspection. According to a letter from Signaller Leslie Creighton, who was in charge of the horses and a cornet player in the regimental band, the unit was inspected by King George, Queen Mary, Lord Kitchener, Winston Churchill, Earl Roberts “and a bunch whom I didn’t recognize”. Signaller Creighton mentioned that while he was being inspected by Lord Kitchener, he stood so stiffly at attention that his feet fell asleep! They began to embark for France in February 1915.

On the 17th of April, the Division moved up to the front line of trenches, just north of Ypres, Belgium. The change of venue could not have been more shocking: the front line was a quagmire of sand and mud, toxic with unburied corpses of men and animals from past encounters, and fouled by rats, fleas, lice and human waste.

From letters written home, the St John Telegraph was able to report on the work of the St. John Signals Company at the front:

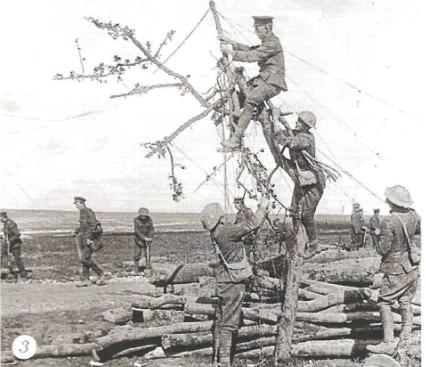

“As the lines of communication between the trenches and the staff lines would be broken by shell fire or otherwise, it was the duty of the signallers to go out at night and make the necessary repairs. Some weeks ago, while Signaller Lelacheur and Creighton and others were up poles performing this work, German bombs were fired in their direction, these bombs burst and illuminated the surroundings …As soon as the bombs would burst the signallers would drop to the ground and seek cover. Whether Signaller LeLacheur had been hit by a sniper or had been wounded while at another duty is not yet learned. His parents and friends will anxiously await further details regarding his condition.”

“As the lines of communication between the trenches and the staff lines would be broken by shell fire or otherwise, it was the duty of the signallers to go out at night and make the necessary repairs. Some weeks ago, while Signaller Lelacheur and Creighton and others were up poles performing this work, German bombs were fired in their direction, these bombs burst and illuminated the surroundings …As soon as the bombs would burst the signallers would drop to the ground and seek cover. Whether Signaller LeLacheur had been hit by a sniper or had been wounded while at another duty is not yet learned. His parents and friends will anxiously await further details regarding his condition.”

Attack of 22 April

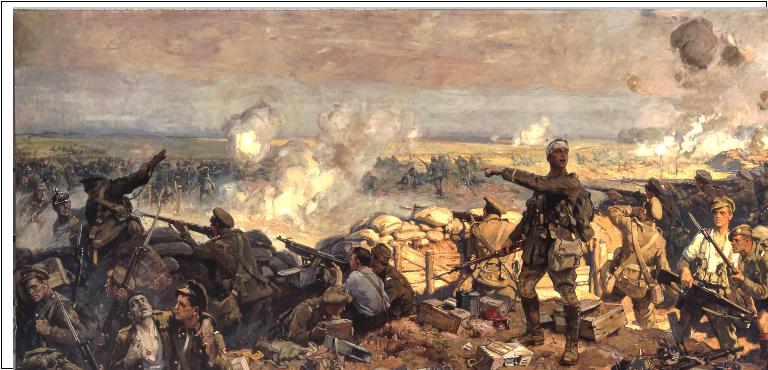

Only 5 days after arriving in the trenches, the Canadians came under a devastating attack. The Germans suddenly launched an artillery barrage that spanned the whole front, from the 45th Algerian Division on the left flank, through the 1st Canadian Division at the centre, to the British 28th Division on the right. Large calibre shells from siege guns pounded the town itself, collapsed buildings and drove civilian refugees southwards, clogging the roads just as fresh troops were moving forward. But the worst was yet to come.

Gas

About an hour after the artillery barrage started, a green-grey cloud of poison gas seeped out of the enemy trenches and drifted slowly toward the French and Algerian lines, through them and beyond.  The Germans had installed more than 5730 canisters of chlorine gas in their front lines, releasing 106 tons of it through rubber hoses, stretched out into no man’s land. The effect on the French front line was instantaneous. Those who could still stand ran screaming and choking rearward until the gas caught up with them. It seeped into trenches and dugouts where they sought shelter.

The Germans had installed more than 5730 canisters of chlorine gas in their front lines, releasing 106 tons of it through rubber hoses, stretched out into no man’s land. The effect on the French front line was instantaneous. Those who could still stand ran screaming and choking rearward until the gas caught up with them. It seeped into trenches and dugouts where they sought shelter.

The chlorine simply exterminated the allied troops in the most horrible way. A three and a half mile gap in the trench line was thus created, into which German infantry poured, just to the left of the Canadian Division.

This attack threatened to encircle both the Canadian and British Divisions.

Many of you will know that the attack was contained, the line held and the German infantry pushed back. This would not have succeeded without the Signallers, fighting their way on foot and horseback, keeping communications intact between the Divisional Headquarters, the Brigades and the forward Battalions. These actions enabled Brigadiers Turner and Currie to redeploy their infantry units to the left flank, call for artillery support and to engage the enemy. But in his diary a few days after the battle, Turner wrote “At 6PM on April 22nd, I really thought all was lost!”

Here is one of the St. John Telegraph’s reports:

TWO SONS AT FRONT – ONE IN YPRES BATTLE

Mrs. Fraser hears Corp. F.W. Fraser Came Through Safely

Cpl. Fraser was a graduate of Mount Allison and a soldier in the 14th Battalion, Royal Montreal Regiment. They were moved forward to repel the enemy in the wake of the gas attack.

He writes “Our Company was in the thick of the big fight and was successful in holding the line for several valuable hours. We were unfortunate in losing all our company’s (B) officers, five in all, besides a non-com and 84 men. Our platoon suffered, perhaps more than any other, as only nine men answered to their names at roll call after they had been relieved. Between April 15 and May 2 we had our boots off only once and during that period enjoyed only a few hours rest. We are now feeling fine and indulging ourselves in long sleeping periods while in reserve.”

You will note that boots and clothing were often mentioned in the soldiers’ letters home, as an understated indication of hardship. More detail may not have passed the military censors. Normally, soldiers in the front trenches were relieved after 4 days or so, and given baths and fresh clothing while resting. – they were to get little of either during this battle.

Counter-Attack of 23 April

In the wake of the gas attack, the enemy advanced into the trenches previously occupied by the French and Algerians, and pushed beyond. This advance was opposed by the Canadian battalions which had turned to face the threat. Hand-to-hand, machine gun and artillery fighting continued throughout the night. Early in the morning of the 23rd a counter –attack was ordered, carried out by the 1st and 4th Battalion of Brigadier Mercer’s 1st Brigade, supported by covering fire of the 1st Canadian Artillery Brigade. According to Max Aitken, later Lord Beaverbrook, these troops suffered terrible casualties, advancing as they were, into withering fire across open ground in broad daylight. But they stopped the enemy, securing and maintaining “during the most critical moment of all, the integrity of the Allied line. It was held against all comers and in the teeth of every conceivable projectile, until the night of Sunday, April 25th, when all that remained of the battalion was relieved by fresh troops.”

Sir Max Aitken goes on. “Captain (sic.) T. E. Powers, of the Signals Company attached to General Mercer’s command, maintained communication throughout, with the advanced line of the attack under a heavy shell fire that cut the signal wires continually. The work of the Company was admirable, and was rendered at the price of many casualties. (Sir Max Aitken, MP, Canada in Flanders, The Official Story of the Canadian Expeditionary Force,Vol 1, Dec 1915)

Attack of 24 April – Gas and Artillery

Meanwhile steady pressure was being applied by the enemy at the apex of the salient held by battalions of General Currie’s 2nd Brigade. At 4am on the 24th of April, the Canadians faced the second chlorine gas attack, followed by an intense artillery barrage that shattered the forward trenches. Soldiers were ordered to use handkerchiefs or bandages, soaked with baking soda, water or urine, as gas masks, but the intensity of the gas was blinding as well. Those not killed instantly were ordered into a fighting withdrawal to a line of trenches to the west of Mercer’s Brigade lines, where they held.

This report from the St John Telegraph:

“In a letter received this morning by Mrs. Powers, wife of Major T.E. Powers, he tells of recent heavy fighting in which he and his unit had taken part on the firing line in France. For eight days they had been in the thick of the fray, and during that time he had not had his clothes off.Though there had been some severe fighting, “hideous in its nature”, all his men and himself had come through safely, except Lou Lelacheur, who had been wounded.”

Major Powers’ letters regularly understated the intensity of the fighting in this and future battles. But details were reported in other letters home, and shared among the families, such as this from St John Signaller W.J. Lloyd to his mother. He said, “…My horse was shot through the nose and legs but I did not get hurt. They were shelling pretty briskly where we were. Major Powers’ horse was hit in six places…”

Another Canadian hero of the Second Battle of Ypres was LCol John McCrae, medical officer of the 1st Canadian Artillery Brigade, in direct fire support of Mercer’s Infantry Brigade, during the counter-attack. In a letter written to his mother, McCrae described the battle as a “nightmare”: “For seventeen days and seventeen nights none of us have had our clothes off, nor our boots even, except occasionally. In all that time while I was awake, gunfire and rifle fire never ceased for sixty seconds….. And behind it all was the constant background of the sights of the dead, the wounded, the maimed, and a terrible anxiety lest the line should give way.” It was after this battle, on May 2nd, that he wrote his famous poem, “In Flanders Fields”. You will all recognize his last verse:

“Take up the quarrel with the foe,

To you from failing hands we throw,

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow,

In Flanders fields.”

John McCrae died in France from pneumonia and meningitis in January, 1918 and was buried in the War Graves Cemetery near Boulogne-Sur-Mer.

But his appeal continues as valid today as it was then, and since upheld by Canada’s soldiers, sailors, airmen and airwomen during the Second World War, Korea, 45 years of the Cold War, the Gulf War, Bosnia, Afghanistan and Libya.

Concluding Remarks

I would like to leave you with a reminder that 100 years ago this August, the St. John Signals Company left the city on the way to the Great War. Next year you will have another reason to pause and reflect on their heroic performance during the Second Battle of Ypres, and how the Canadians held the line in the first gas attack in the history of warfare. This account should put to rest any doubt that Signals, by whichever name, rightfully belongs among the Combat Arms.Yours is a distinguished heritage, you have earned your Battle Honours and your place in Canadian history. Canada is proud of you all, and I know that your first Commanding Officer, Thomas Edward Powers would be proud of you, too.

May God bless the 37th Signals Regiment and all who serve in it….

Thank you….”